- Foreword xi

- Preface xv

- Acknowledgments xix

- Homage to Manjushri xxi

- Introduction 1

- 1. THE CAUSE: Buddha Nature 7

- 2. THE BASIS: A Precious Human Life 15

- 3. THE CONDITION: The Spiritual Friend 23

- Why We Need a Spiritual Friend 24

- The Different Categories of Spiritual Friends 25

- The Qualities of Ordinary Spiritual Friends 26

- The Master-Disciple Relationship 27

- Receiving the Teachings in the Right Way 29

- 4. THE METHOD: The Instructions of the Spiritual Friend 37

- First Antidote: Contemplating Impermanence 32

- Second Antidote 37

- Contemplating the Misery of Samsara 37

- Understanding Karma 44

- Third Antidote: Love and Compassion 50

- The Development of Loving-Kindness 51

- The Development of Compassion 60

- Fourth Antidote: Bodhichitta 64

- The Bodhichitta of Aspiration 67

- Refuge 67

- Taking Refuge in the Buddha 68

- Taking Refuge in the Dharma 70

- Taking Refuge in the Sangha 70

- The Three Kayas 72

- The Refuge Ceremony 74

- The Bodhichitta of Commitment 76

- The Bodhisattva Vows 76

- Instructions for Developing the Bodhichitta of Commitment: The Six Paramitas 80

- First Paramita: Generosity 82

- Second Paramita: Ethics or Right Conduct 87

- Third Paramita: Forbearance 88

- Fourth Paramita: Diligence 93

- Fifth Paramita: Meditation 99

- Sixth Paramita: Wisdom 108

- The Five Levels of the Bodhisattva Path 138

- Accumulation 139

- Integration 140

- Insight 141

- Meditation 142

- Complete Accomplishment 142

- The Ten Bodhisattva Levels 143

- 5. THE RESULT: Perfect Buddhahood149

- 6. The Activities of a Buddha 163

- Conclusion 169

- Dedication of Merit 171

- Notes 173

- Index 179

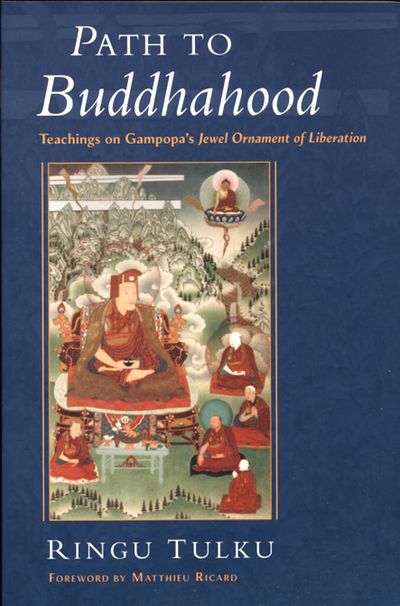

The Dagpo Tarjen[1] or The Jewel Ornament of Liberation[2] of Gampopa is one of the most important texts of Tibetan Buddhism. In the Kagyu[3] tradition it is the main text used in the instruction of monks. It is sometimes referred to as the "merging of the two streams" because Gampopa here combines two traditions or currents of Dharma teachings, that of the Mahayana Kadampa[4] tradition and that of the tantric Mahamudra[5] tradition.

Gampopa's teachings brought these two traditions together in such a way that they could be practiced together as one experience. They quickly became one of the most important and effective foundation texts used in the teaching of Buddhism in Tibet from the eleventh century onward. The whole Kagyu tradition is based mainly on this teaching.

The Author

Gampopa was born in 1079 and died in 1153. Despite his renown as a physician, he was unable to save his wife and two children, who died in an epidemic that ravaged the region where they lived. Full of grief, he came to a deep understanding of the transitory nature of all things and the inherent suffering that this implied. He renounced the world and devoted himself totally to spiritual practice, seeking a way out of the suffering of samsara. Gampopa became a monk and for many years followed the teachings of the Kadampa geshes[6] of the time. One day he happened to hear the name of Milarepa, the famous Tibetan yogic poet, and intense devotion immediately arose in him. Deeply inspired, he began to cry and left at once to seek out Milarepa.

After many hardships Gampopa arrived near the place where the yogi was staying. Having traveled without any rest, Gampopa was by now ill and exhausted. The people in the local village took him in and treated him with great respect and hospitality. "You must be the one whom Milarepa spoke of," they said. "What did he say about me?" asked Gampopa. The villagers replied that Milarepa had predicted his arrival, telling them, "A monk from Ü[7] is coming. He is a very great bodhisattva and will be the holder of my lineage. Whoever shows him hospitality when he first arrives will be liberated from samsara and will enjoy the best of good fortune."

When Gampopa heard this, he said to himself, "I must be a very special person." Feelings of pride and conceit arose in his mind, and, consequently, when he went to meet Milarepa in his cave, the latter refused to see him. He had Gampopa wait in a nearby cave for fifteen days. When he was finally allowed to see Milarepa, Gampopa found the yogi sitting there with a skull cup full of wine. He handed the skull to Gampopa and invited him to drink. Gampopa was perplexed. He was a fully ordained monk and as such had vowed to abstain from alcohol. Yet here was Milarepa commanding him to drink. It was unthinkable! So great, however, was Gampopa's trust and devotion to his guru that he took the skull cup and drained it of every drop.

This act had a very nice and auspicious significance, as it showed that Gampopa was completely open and ready to receive the entirety of Milarepa's teachings and full realization. It is said that how much a student can benefit from a teacher depends upon how open he or she is. Although Gampopa was a very good monk, he drank the skull cup of wine without any hesitation or reservation, which signified that he was completely open and without the slightest doubt.

Milarepa subsequently gave Gampopa his complete teachings, and within a very short time Gampopa became his best and most realized student.[8] In Gampopa's teachings we therefore find the scholarly erudition and discipline of his monastic tradition combined with the total realization of a fully accomplished yogi, which he received through Milarepa.

The present commentary relies mainly on the original Tibetan text but draws upon both Guenther's and Holmes's translations where necessary.